Contents

- 📍 Where Fat Is Stored Matters

- ⚖️ Fat Cell Development Over Time

- 🧬 Types of Body Fat: More Than Just Storage

- 📍 Where Is Body Fat Stored? Subcutaneous vs. Visceral Fat

- ❓ How Do I Get Rid of Belly Fat?

- ⚖️ Measuring Body Fat: What You Need to Know

- 🧠 Bottom Line:

- ⚖️ Body Mass Index (BMI)

- 📊 Interpreting the BMI Number

- 📏 Waist Circumference: A Telling Measure of Health

- 🔄 Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR): Measuring Fat Distribution

- 📏 Waist-to-Height Ratio (WHtR): A Simple Risk Indicator

- 🧪 Additional Measures of Body Fat

- ⚖️ Is It Healthier to Be Overweight Than Underweight?

While body fat often gets a bad reputation, especially in a culture focused on thinness, it actually plays a vital role in maintaining health. Fat tissue is not just a passive storage site—it’s a dynamic and complex organ that interacts with the rest of the body in important ways.

🔬 Fat as an Endocrine Organ

Adipose tissue is metabolically active. It produces hormones and signaling molecules (called adipokines) that affect:

- Appetite regulation – Leptin, for example, signals the brain to reduce hunger.

- Insulin sensitivity – Adiponectin improves the body’s sensitivity to insulin.

- Inflammation and immune response – Fat stores house immune cells like macrophages, which can trigger inflammation in response to excess fat storage.

Chronic low-grade inflammation caused by overaccumulation of fat—especially visceral fat—can impair normal metabolic functions, contributing to insulin resistance, elevated blood sugar, and increased risk of chronic conditions.

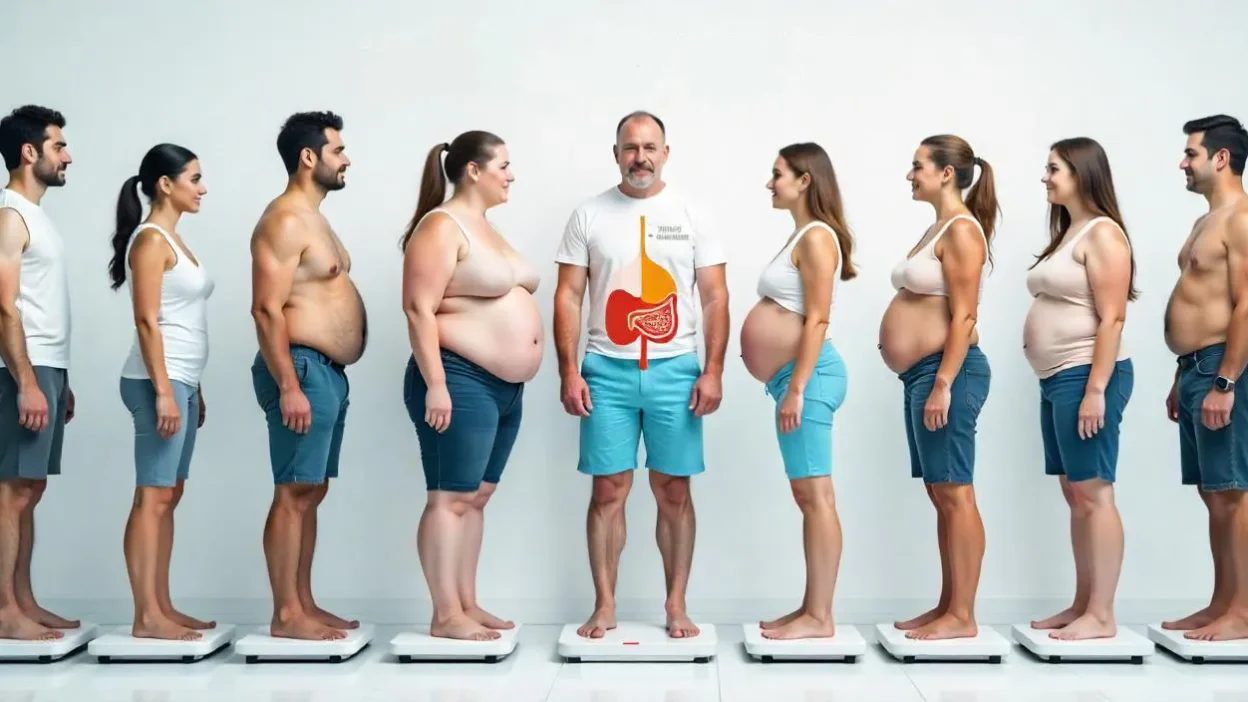

📍 Where Fat Is Stored Matters

Subcutaneous Fat

This is the fat located just beneath the skin, typically found in the thighs, hips, and arms. It’s generally less harmful and in some cases, may even have protective metabolic effects.

Visceral Fat

Stored deep within the abdominal cavity around internal organs, this type of fat is strongly linked with increased risk for cardiovascular disease, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome. Visceral fat is more hormonally active and inflammatory than subcutaneous fat.

⚖️ Fat Cell Development Over Time

The number of fat cells is largely determined in childhood and adolescence. Once established, the body maintains this number, even with weight loss—meaning fat cells shrink but don’t disappear. This is one reason why weight regain is common: the body is wired to fill those empty fat cells again.

However, significant lifestyle changes—regular exercise, a balanced diet, stress reduction—can reduce inflammation and improve metabolic health, even without dramatic changes in weight.

🧬 Types of Body Fat: More Than Just Storage

Not all fat is the same—and understanding the different types helps shed light on how fat functions in our bodies beyond just storing energy.

🟤 Brown Fat

- Function: Burns calories to generate heat (a process called thermogenesis).

- Who has it? Most abundant in infants but still present in adults in smaller amounts.

- Health impact: Stimulated by cold exposure and exercise, brown fat is considered metabolically healthy.

- Fun fact: People with obesity often have less brown fat than lean individuals.

⚪ White Fat

- Function: Stores energy and secretes over 50 hormones and molecules, including:

- Leptin (regulates hunger)

- Adiponectin (enhances insulin sensitivity)

- Location: Belly, hips, thighs.

- Health impact: In excess, it contributes to inflammation, insulin resistance, and metabolic disease.

🟤➡️⚪ Beige Fat

- Function: White fat cells that can transform to behave like brown fat.

- How? Through cold exposure or physical activity.

- Health impact: Encouraging the “browning” of white fat may improve metabolism.

🌸 Pink Fat

- Function: Found in pregnant and lactating women, this fat helps produce and secrete breast milk.

- Transformation: Derived from white fat that shifts during pregnancy to support breastfeeding.

🌟 Essential Fat

- Function: Supports vital organ function, hormone regulation, temperature control, and nutrient absorption.

- Location: Found in the brain, nerves, muscles, and organs.

- Warning: Dropping below 5% (men) or 10% (women) body fat can impair bodily function.

📍 Where Is Body Fat Stored? Subcutaneous vs. Visceral Fat

Fat doesn’t just vary by type—it matters where it’s stored in your body. The location of fat plays a major role in your overall health.

✋ Subcutaneous Fat – Just Beneath the Skin

- What it is: The layer of fat you can pinch—located under the skin.

- Function: Cushions bones and joints, helps regulate temperature.

- Common areas: Waist, hips, thighs, upper back, buttocks.

- Health note: Most abundant type of fat. While excess amounts can increase disease risk, it’s generally less harmful than visceral fat.

⚠️ Visceral Fat – The “Hidden” Risk

- What it is: White fat that surrounds internal organs like the liver, intestines, pancreas, and even the heart.

- Health impact: Associated with a greater risk of:

- Cardiovascular disease

- Type 2 diabetes

- Certain cancers

- Why it matters: Visceral fat secretes inflammatory cytokines that contribute to insulin resistance and chronic inflammation.

❓ How Do I Get Rid of Belly Fat?

Let’s clear up a common myth:

You can’t “spot reduce” fat. Doing sit-ups won’t magically target belly fat—but you can lose it overall.

✅ What Works:

- Caloric balance: Create a calorie deficit through portion-controlled meals and nutrient-dense foods.

- Exercise regularly: Aim for a mix of cardio (like walking or cycling) and strength training.

- Avoid sugary drinks: Especially soda and sweetened beverages, which are linked to visceral fat gain.

- Sleep well: Inadequate sleep is strongly linked to increased abdominal fat.

- Manage stress: Chronic stress elevates cortisol, which is tied to more belly fat storage.

🧠 Note: Weight loss generally happens across the body, not just in one area—but a consistent lifestyle change can significantly reduce dangerous visceral fat over time.

⚖️ Measuring Body Fat: What You Need to Know

Obesity isn’t just about weight—it’s about body fatness, and not all body fat is created equal. That’s why health professionals use various methods to estimate body fat levels. Each method has its pros and cons, and using more than one may offer a clearer picture of health risk.

🧮 Common Methods to Measure Body Fat

1. Body Mass Index (BMI)

- What it is: A ratio of weight to height (kg/m²).

- Pros: Easy, quick, and widely used to screen for weight categories.

- Cons: Doesn’t differentiate between fat and muscle. A muscular person might be misclassified as overweight.

2. Waist Circumference

- What it measures: Abdominal fat (visceral fat).

- Pros: Better indicator of health risk than weight alone.

- Risk thresholds:

- Women: >35 inches (88 cm)

- Men: >40 inches (102 cm)

3. Waist-to-Hip Ratio

- What it does: Compares waist size to hip size to assess fat distribution.

- Higher ratio = Higher risk of heart disease and metabolic issues.

4. Skinfold Calipers

- How it works: Measures thickness of fat at various body sites.

- Pros: Low-cost and accessible.

- Cons: Requires a skilled practitioner; can be less accurate in those with obesity.

5. Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA)

- What it is: Sends a weak electrical current through the body to estimate body composition.

- Used in: Smart scales, handheld devices.

- Cons: Accuracy can vary depending on hydration and device quality.

6. Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA)

- Gold standard for body composition analysis.

- Measures: Total body fat, lean mass, and bone density.

- Cons: Expensive and typically used in clinical or research settings.

7. Hydrostatic Weighing and Air Displacement Plethysmography (e.g., Bod Pod)

- Pros: Accurate scientific measures.

- Cons: Less accessible, requires specialized equipment.

🧠 Bottom Line:

- No single method is perfect.

- For most people, waist circumference + BMI gives a practical starting point.

- For deeper insights (especially in clinical settings), methods like DEXA or BIA can be more revealing.

⚖️ Body Mass Index (BMI)

🔍 Why Use BMI?

The Body Mass Index (BMI) is one of the most widely used tools to estimate body fat and assess weight-related health risks. It provides a simple ratio of weight to height and is calculated as:

BMI = (weight in pounds ÷ height in inches²) × 703

While BMI doesn’t directly measure fat, it often correlates well with more accurate methods like hydrostatic (underwater) weighing and DEXA scans—which are expensive and less accessible.

Because it’s noninvasive, inexpensive, and easy to use, BMI is commonly used in:

- Clinical settings

- Population-level research

- National health surveys to track obesity trends

⚠️ BMI Limitations

Despite its widespread use, BMI is not a perfect tool. It measures weight, not fat distribution or body composition. It also does not differentiate between:

- Fat mass

- Muscle mass

- Bone density

And it doesn’t show where fat is located—such as visceral (belly) fat, which carries greater health risk.

BMI may be influenced by:

- Age: Older adults usually carry more fat even with lower BMIs.

- Sex: Women naturally have more body fat than men.

- Ethnicity:

- Black individuals tend to have more lean muscle at the same BMI.

- Southeast Asians may appear healthy by BMI but still carry harmful visceral fat and face metabolic risks.

- Fitness level: Athletes can have high BMIs due to muscle, not fat.

- Bone structure: People with larger frames may weigh more due to heavier bones, not excess fat.

✅ When to Use BMI

- Best used as a screening tool, not a diagnostic test.

- Helpful when supplemented with other measurements:

- Waist circumference

- Waist-to-hip ratio

- Body fat percentage

These additional tools help paint a more complete picture of metabolic health and fat distribution.

📏 How to Calculate BMI

Use this formula:

BMI = (Weight in lbs ÷ Height in inches²) × 703

Or use a BMI calculator for convenience.

Example:

A person who weighs 170 lbs and is 5’7” (67 inches) tall:

BMI = (170 ÷ 67²) × 703 = 26.6

This BMI falls in the “overweight” category.

📊 Interpreting the BMI Number

🌐 WHO BMI Classifications

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines weight categories based on BMI as follows:

| Category | BMI Range (kg/m²) |

|---|---|

| Underweight | Less than 18.5 |

| Normal weight | 18.5 – 24.9 |

| Overweight (Pre-obesity) | 25.0 – 29.9 |

| Obesity Class I | 30.0 – 34.9 |

| Obesity Class II | 35.0 – 39.9 |

| Obesity Class III | 40.0 and higher |

💡 Note: These classifications are useful at the population level but should be interpreted with caution at the individual level, especially when not considering age, ethnicity, muscle mass, and underlying health conditions.

⚠️ The Link Between BMI and Mortality

Research has consistently shown that a BMI outside the normal range—whether too low or too high—is associated with an increased risk of early death and chronic disease.

🔍 Key Studies:

1. New England Journal of Medicine Meta-Analysis

- Found a U-shaped relationship between BMI and all-cause mortality.

- The lowest death rate occurred in individuals with a BMI of 22.5 to 24.9.

- Higher mortality rates were observed in:

- Underweight individuals (BMI <18.5)

- Overweight and obese individuals (BMI >25)

- This analysis excluded confounding groups, such as:

- Smokers (who tend to weigh less)

- Individuals with pre-existing chronic illness (e.g., cancer, heart disease)

- Adults over age 85 (frailty can distort BMI readings)

2. The Lancet Meta-Analysis

- Data from over 10 million people across four continents.

- For every 5-unit increase in BMI above 25, the risk of premature death increased by 31%.

- Cardiovascular mortality: +49%

- Respiratory disease mortality: +38%

- Cancer mortality: +19%

- This study also excluded confounding variables (smokers, chronically ill participants, and early deaths).

❗ Beware of Methodological Bias

Some earlier studies seemed to suggest that having overweight or mild obesity might lower the risk of death. However, many of those findings were distorted by:

- Reverse causation: Where low weight is due to serious illness rather than a cause of health.

- Smoking: Smokers tend to weigh less and have higher mortality, skewing the results.

- Failure to exclude early deaths: Which may result from conditions that cause weight loss.

Modern, well-controlled studies that account for these biases show that a BMI above 25 consistently increases the risk of premature mortality.

📏 Waist Circumference: A Telling Measure of Health

Why Waist Size Matters

Unlike Body Mass Index (BMI), which reflects overall weight, waist circumference specifically addresses visceral fat—the deep belly fat that surrounds internal organs. This type of fat is strongly associated with:

- Insulin resistance

- Inflammation

- Metabolic disorders

- Cardiovascular disease

- Increased risk of death—even in people with a “normal” BMI

👉 In fact, waist circumference may be a more accurate predictor of early mortality and chronic disease than BMI alone—especially in people who do not appear overweight.

🔬 What the Research Says

🧪 Nurses’ Health Study

- Tracked 44,000+ healthy middle-aged women over 16 years.

- Women with waists ≥35 inches had nearly double the risk of dying from heart disease, compared to those with waists <28 inches.

- These women also had significantly higher risk of death from cancer and all causes.

- Importantly, normal-weight women (BMI <25) with larger waists also faced 3x higher risk of death from heart disease than their leaner-waisted counterparts.

🧪 Shanghai Women’s Health Study

- Found similar patterns in normal-weight women: those with larger waists had increased all-cause mortality, even when BMI was within the “normal” range.

📐 How to Measure Your Waist Properly

- Wear light clothing or none at all.

- Stand upright, relaxed, and exhale normally.

- Place a flexible measuring tape around your middle, crossing your navel (belly button).

- The tape should lie flat against the skin—not too loose, but not pressing into the skin.

- Record your measurement. Repeat 2–3 times for consistency.

🚨 Health Risk Thresholds (per NIH guidelines):

| Sex | Increased Health Risk |

|---|---|

| Men | Waist > 40 inches |

| Women | Waist > 35 inches |

📌 Takeaway: Even if your BMI is normal, increasing waist size can be a red flag—and is worth discussing with your healthcare provider.

🔄 Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR): Measuring Fat Distribution

What It Measures

The waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) is another simple yet effective tool used to estimate abdominal obesity—a key indicator of chronic disease risk. Like waist circumference, WHR reflects visceral fat, but also considers body shape by factoring in hip size.

💡 Why WHR Matters

- WHR is a strong predictor of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and early mortality.

- Some experts believe WHR may offer more context than waist circumference alone, since waist size can vary by body frame.

- However, a major study found that WHR and waist circumference are equally effective at predicting death from heart disease, cancer, and all causes.

⚠️ High WHR can result from either too much abdominal fat or low muscle mass around the hips—both carry health risks.

🌍 Ethnic Differences in WHR

WHR cutoffs for defining abdominal obesity can vary by ethnicity. For example:

- Asian populations tend to have higher metabolic risk at lower levels of BMI or WHR.

- Therefore, Asian women have a WHR cutoff of 0.80 or less, compared to 0.85 for Caucasian women.

| Group | Abdominal Obesity (WHR Cutoff) |

|---|---|

| Men | > 0.90 |

| Women (Caucasian) | > 0.85 |

| Women (Asian) | > 0.80 |

📏 How to Measure WHR

- Measure your waist at the narrowest point (usually just above the navel), following the same instructions as waist circumference.

- Measure your hips at the widest part of your buttocks.

- Calculate WHR:

Divide your waist measurement by your hip measurement (Waist ÷ Hips = WHR)

🧠 Example:

If your waist is 32 inches and hips are 40 inches:

32 ÷ 40 = 0.80

🧪 What Your WHR Means

- A lower WHR indicates more fat stored in the hips/thighs (pear shape), which is generally associated with lower health risks.

- A higher WHR indicates more fat stored in the abdominal area (apple shape), associated with increased risk of chronic diseases.

📏 Waist-to-Height Ratio (WHtR): A Simple Risk Indicator

What Is WHtR?

The waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) is a straightforward, low-cost screening tool used to assess visceral abdominal fat, which is linked to serious health risks like:

- Cardiometabolic diseases (e.g., hypertension, diabetes)

- Heart disease

- Premature death

Even if your BMI falls within a normal range, a high WHtR may reveal hidden risk.

✅ Why WHtR Is Useful

- WHtR is more sensitive than BMI in predicting health risks related to abdominal fat.

- It’s particularly helpful for identifying “normal-weight obesity” (having a normal BMI but excess visceral fat).

- It provides one consistent threshold across sexes and ethnicities.

Rule of Thumb:

Your waist should be less than half your height.

📐 How to Calculate WHtR

- Measure your waist circumference (in inches or cm).

- Measure your height in the same unit.

- Divide your waist by your height.

🧠 Formula:

WHtR = Waist (in) ÷ Height (in)

or

WHtR = Waist (cm) ÷ Height (cm)

🔍 How to Interpret WHtR

| WHtR Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| < 0.5 | Low risk |

| ≥ 0.5 | Elevated risk of metabolic disease |

| > 0.6 | High risk; action recommended |

🧪 Example:

If your waist is 34 inches and height is 68 inches:

34 ÷ 68 = 0.5 → at the risk threshold

🧪 Additional Measures of Body Fat

While tools like BMI and waist measurements are commonly used to estimate body fat and health risk, there are additional methods—some more specialized or used in clinical settings. These can provide more direct estimates of body fat percentage.

✋ Skinfold Thickness

What it is:

A method that uses calipers to pinch and measure the thickness of subcutaneous fat (the fat under the skin) at various standardized locations on the body, such as:

- Triceps (back of the upper arm)

- Biceps (front of the upper arm)

- Subscapular (under the shoulder blade)

- Suprailiac (above the hip bone)

- Abdomen, thigh, and chest

How it works:

Measurements are taken at three or more sites, then entered into prediction equations to estimate total body fat percentage.

Pros:

- Inexpensive and portable

- Can be used in both clinical and fitness settings

- Offers a more direct estimate of body fat than BMI

Cons:

- Accuracy depends heavily on the skill of the person taking the measurements

- Calipers have limited range, which may make them unsuitable for individuals with higher body fat

- Not useful for measuring visceral fat or fat distribution deep within the body

📌 Best for: Fitness professionals, routine assessments, individuals without severe obesity

⚡ Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA)

What it is:

BIA devices estimate body composition by sending a low-level, painless electrical current through the body. Because fat tissue resists electrical flow more than lean tissue (which contains more water), the device measures this resistance (or “impedance”) and uses equations to estimate:

- Body fat percentage

- Lean body mass

- Total body water

How it works:

The individual typically stands barefoot on a scale-like device or holds sensors in their hands. Multi-frequency and multi-site BIA devices (which use both hand and foot sensors) tend to be more accurate than single-site versions.

Pros:

- Quick, non-invasive, and painless

- Portable and user-friendly; available for home and professional use

- Relatively affordable

Cons:

- Accuracy may be affected by hydration status, recent exercise, or food and fluid intake

- Illness, dehydration, or rapid weight loss can distort body water balance and skew results

- Less accurate than more advanced imaging methods like DEXA

📌 Best for: General tracking of body composition over time, especially when used consistently under the same conditions

🌊 Underwater Weighing (Hydrostatic or Densitometry)

What it is:

This method involves weighing a person on dry land, and then again while fully submerged in water. The difference in these two measurements allows researchers to calculate:

- Body volume

- Body density

- Body fat percentage

How it works:

Fat tissue is less dense than water, so it floats more easily. In contrast, lean tissue (like muscle) is denser and sinks. If someone weighs more underwater, it means they likely have more lean mass and less fat. Conversely, someone with higher fat mass will weigh less underwater.

⚖️ Formula applied: Greater underwater weight = higher body density = lower body fat percentage.

Pros:

- Very accurate method; considered a “gold standard” for body composition

- Useful in clinical and research settings

Cons:

- Expensive, requires specialized equipment

- Not widely accessible outside research or sports labs

- Can be uncomfortable (requires full submersion and exhaling completely underwater)

- Not suitable for people with certain health conditions or water anxiety

📌 Best for: Research studies or athletes needing precise body composition data

💨 Air-Displacement Plethysmography (e.g., Bod Pod)

What it is:

This method is based on the same principle as underwater weighing, but it uses air instead of water to measure body composition. One widely known device is the Bod Pod.

How it works:

You sit inside a small, egg-shaped chamber wearing minimal clothing (like a bathing suit or compression gear). The machine measures changes in air pressure to determine your body volume. When combined with your weight, it can calculate your body density and body fat percentage.

⚖️ Like underwater weighing, the more body fat you have, the lower your body density will be.

Pros:

- Accurate and reliable body composition measurements

- Quick and non-invasive

- No need for water—ideal for those uncomfortable with submersion

- Suitable for children, elderly individuals, and people with medical limitations

Cons:

- Expensive and typically found only in research or specialized fitness centers

- Requires access to a dedicated facility with the equipment

📌 Best for: Those seeking precision in body fat measurement without the discomfort of water-based methods

⚖️ Is It Healthier to Be Overweight Than Underweight?

While being severely underweight can pose serious health risks—especially due to conditions like eating disorders or chronic illnesses—studies show that carrying excess weight is also linked to increased risk of premature death and chronic disease.

- U-shaped mortality curve: Both underweight and overweight individuals show higher mortality rates than those within a mid-range BMI.

- Confounding factors: Many studies that suggest thinness is riskier may be flawed by including smokers or people with undiagnosed illnesses that cause weight loss.

- Strong evidence: Large, well-designed studies consistently show that higher body weight correlates with increased risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and early death—even after accounting for smoking and illness.

Bottom line: A BMI below 18.5 is generally considered underweight, but may be normal for some people if it’s stable and not caused by illness. Unintentional weight loss, however, is always a red flag and should be evaluated by a doctor.

Whoa, mind blown! Always thought fat was just…well, fat. This completely changes my perspective. So it’s basically a mini-organ with a bunch of important jobs? Makes you rethink those “fat-free” everything fads, huh? Thanks for the info!