Contents

- 🍕 Cut Back on Prepared Foods

- 🍲 Eat Smaller Portions of Salty Foods

- 🧂 Discover Reduced or No-Sodium Alternatives

- 🏷️ Know Your Labels: “Low-Sodium” vs. “Reduced Sodium”

- 💰 Burden on Public Health and Health Care Spending

- 🇺🇸 U.S. Initiatives to Reduce Sodium Intake

- 🛠️ Other Key Recommendations for Reducing Sodium Intake

- 🌍 International Initiatives: Leading the Way in Sodium Reduction

High blood pressure often begins in childhood, and developing a taste for salty foods at a young age can lead to long-term health issues. Children who grow up eating processed or heavily salted foods may have a harder time adjusting to lower-sodium diets later in life. That’s why it’s essential to begin healthy habits early—reducing sodium intake in childhood helps train taste preferences and sets the foundation for a healthier adulthood.

But the benefits aren’t limited to kids. Reducing sodium intake can significantly lower blood pressure in adults of all ages—even those who are not hypertensive. Whether you’re 8 or 80, making mindful choices around salt can improve heart health, reduce stroke risk, and support kidney function.

🍕 Cut Back on Prepared Foods

Roughly 70% of the sodium Americans consume comes from processed and restaurant foods—not the salt shaker. Everyday items like crackers, deli meats, canned soups, breads, cheeses, and even breakfast cereals can pack in more sodium than you’d expect.

Surprisingly, foods that don’t even taste salty—like certain cereals or baked goods—can be significant sodium contributors simply because we eat them so frequently. Bread, for example, may not seem salty, but eating several slices throughout the day can add up quickly.

According to the CDC, some of the biggest sodium sources in the American diet include:

- Breads and rolls

- Cold cuts and cured meats

- Pizza

- Chicken (fresh and processed)

- Soups

- Sandwiches

- Cheese

- Egg dishes

- Packaged snacks like chips and crackers

- Sauces, gravies, and salad dressings

🧂 The good news? Your taste buds won’t miss much. Most people can’t detect a 30% reduction in salt, so choosing lower-sodium products—or cutting back a bit in recipes—won’t sacrifice flavor. That gives home cooks, chefs, and food companies a huge opportunity to help reduce sodium intake without sacrificing taste.

🍲 Eat Smaller Portions of Salty Foods

You don’t need to eliminate all high-sodium favorites to eat healthfully. Instead of cutting out traditional or beloved salty foods altogether—like soy sauce in Chinese cuisine, salted pickles and fish in Japanese meals, or feta cheese and olives in Mediterranean diets—focus on portion size.

🧂 These foods can still be part of a balanced diet when eaten in moderation. For example:

- Use a light drizzle of soy sauce instead of soaking your dish.

- Add a few olives or a small sprinkle of cheese for flavor rather than making them the main ingredient.

- Choose low-sodium or reduced-sodium versions when available.

Cultural eating patterns often include fresh fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats that can help balance sodium intake. So, rather than eliminating foods you love, enjoy them in smaller amounts while emphasizing nutrient-rich, whole-food ingredients in the rest of your meal.

🧂 Discover Reduced or No-Sodium Alternatives

Cutting back on salt doesn’t have to mean sacrificing flavor. There are plenty of delicious, low- or no-sodium options that can elevate meals without the health risks of excess sodium.

🌿 Herbs and spices like garlic, black pepper, paprika, cumin, rosemary, basil, and chili flakes can replace salt in most savory dishes.

🍋 Citrus fruits—especially lemon and lime—are powerful tools for flavor enhancement. Interestingly, citrus and sodium activate similar taste receptors, meaning a splash of lemon can make food taste saltier—even with less actual sodium.

🛒 When shopping, look for:

- Low-sodium or sodium-free versions of soups, sauces, dressings, and canned goods.

- Salt substitutes, which are usually made with potassium chloride.

💡 Note about potassium-based substitutes:

- Sodium-free substitutes typically contain 100% potassium chloride.

- “Lite” salts often combine sodium chloride with potassium chloride.

- Potassium chloride tastes similar to salt, but can have a bitter aftertaste when cooked, so it’s better used at the table rather than in recipes.

⚠️ Important: Potassium chloride is not safe for everyone. Consult your doctor before using salt substitutes if you:

- Have kidney disease or diabetes

- Are on medications like ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), or potassium-sparing diuretics

- Have had urinary flow issues

By experimenting with flavorful alternatives and being mindful of your health conditions, you can lower your sodium intake without compromising taste.

🏷️ Know Your Labels: “Low-Sodium” vs. “Reduced Sodium”

When navigating food packaging, it’s important to understand what sodium-related claims actually mean:

- ✅ “Low-sodium” means the food contains 140 mg of sodium or less per serving, as defined by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

- ⚠️ “Reduced,” “less,” or “lower sodium” only means that the food contains at least 25% less sodium than the regular version—but it can still be high in sodium overall.

🔎 Real-world examples:

- “Less-sodium” soy sauce still packs a punch with about 550 mg of sodium per tablespoon, compared to 1,000 mg in the regular version.

- A “lower-sodium” deli turkey may contain 380 mg per serving, only slightly less than the 450 mg in the standard variety.

🧠 Tip: Don’t rely on front-of-package claims. Always read the Nutrition Facts label to know the exact sodium content per serving—and how it fits into your daily intake goals.

🍳 Cook Your Own Meals: Control the Salt, Keep the Flavor

One of the most effective ways to reduce sodium intake is by cooking more meals at home using fresh, minimally processed ingredients. When you cook your own food, you control exactly how much salt—if any—goes into each dish.

Instead of relying on the sodium-heavy flavors of processed foods or restaurant meals, try building flavor using:

- Fresh or dried herbs and spices

- Citrus juices (lemon, lime, orange)

- Aromatics like garlic, onion, and ginger

- Natural umami boosters like mushrooms or tomato paste

🥦 Recipe Inspiration:

✨ Cardamom Roasted Cauliflower

Roasting cauliflower creates a naturally sweet, caramelized flavor. This version is seasoned with cardamom and lemon juice—bringing depth and brightness without added salt.

✨ Citrus Salad with Ginger Lime Dressing

A colorful, refreshing option for a side or light dessert. This dressing—made with lime juice and fresh ginger—also pairs beautifully with baby greens like spinach or arugula, skipping the sodium-laden bottled dressings.

💰 Burden on Public Health and Health Care Spending

Hypertension affects 9 out of 10 U.S. adults at some point in their lives—making it one of the most prevalent and costly health conditions nationwide. The economic toll is enormous, with $73.4 billion spent in direct and indirect health care costs in 2009 alone.

But the good news? Even modest reductions in sodium intake could lead to massive health and economic benefits:

- 🧂 Reducing daily sodium to 2,300 mg (about 1 teaspoon of salt) could prevent 11 million cases of hypertension and save $18 billion annually in health care costs.

- 🧂 Cutting sodium by just 1,200 mg daily (½ teaspoon) could:

- Prevent up to 99,000 heart attacks

- Prevent 66,000 strokes

- Save 92,000 lives each year

- Reduce health costs by $24 billion annually

📉 Even smaller reductions in sodium consumption would still be cost-effective and lifesaving, especially in developed countries, where sodium overconsumption is more pronounced.

While some food companies have begun reformulating products, achieving population-level sodium reduction will also require policy support, government leadership, and continued public awareness efforts.

🇺🇸 U.S. Initiatives to Reduce Sodium Intake

Despite growing concerns over sodium’s health effects, there is currently no legal limit on the amount of sodium allowed in foods. This is largely because salt has long held the designation of “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS)—a status increasingly questioned in light of decades of research linking excess sodium to high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease.

In 2010, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a groundbreaking report, Strategies to Reduce Sodium Intake in the United States, urging a major shift:

🔹 The FDA should begin regulating sodium levels in commercially prepared foods, which account for about 75% of the salt Americans consume.

🔹 The goal is not a ban on salt, but rather a gradual, stepwise reduction that would be imperceptible to the consumer palate.

The IOM recommended that:

- The FDA work collaboratively with food manufacturers to set sodium limits in key food categories.

- These limits would be phased in over several years, possibly over a 10-year period, according to FDA sources cited by The Washington Post.

💬 “Involving the FDA would help create and maintain a level playing field for food companies,” says Dr. Walter Willett, Professor of Epidemiology and Nutrition at Harvard.

Voluntary limits could backfire, he notes, as some companies might increase salt to stand out in taste, undercutting responsible efforts. FDA regulation would ensure uniformity and protect industry leaders making health-conscious changes.

🛠️ Other Key Recommendations for Reducing Sodium Intake

To support national efforts aimed at lowering sodium consumption, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) proposed several policy and public health strategies beyond FDA regulation:

🏷 Update Nutrition Labels

- Adjust the Daily Value for sodium from 2,300 mg to 1,500 mg.

- This change would give consumers a clearer benchmark for what qualifies as high sodium.

- It would also motivate food manufacturers to lower sodium levels to avoid warning labels or negative consumer perceptions.

📢 Launch a Nationwide Awareness Campaign

- Industry-wide sodium reduction helps, but consumer education is essential.

- A coordinated public health campaign could:

- Promote low-sodium diets

- Offer tips for label reading and meal planning

- Shift taste preferences away from overly salty foods

⚖️ Barriers to Progress

Despite evidence-based recommendations from the IOM—an independent, nonprofit body recognized for its rigorous health guidance—implementation is not guaranteed. The salt industry has historically resisted regulation, often arguing that sodium’s impact on blood pressure is overstated.

🏙️ Case Study: New York City’s Sodium Strategy

One promising example is the National Salt Reduction Initiative (NSRI), spearheaded by New York City’s Department of Health:

- Voluntary collaboration with food manufacturers and restaurants

- Goal: Reduce sodium in packaged and restaurant foods by 25% over 5 years

- If successful, this effort could:

- Cut national sodium intake by 20%

- Prevent thousands of premature deaths due to heart disease and stroke

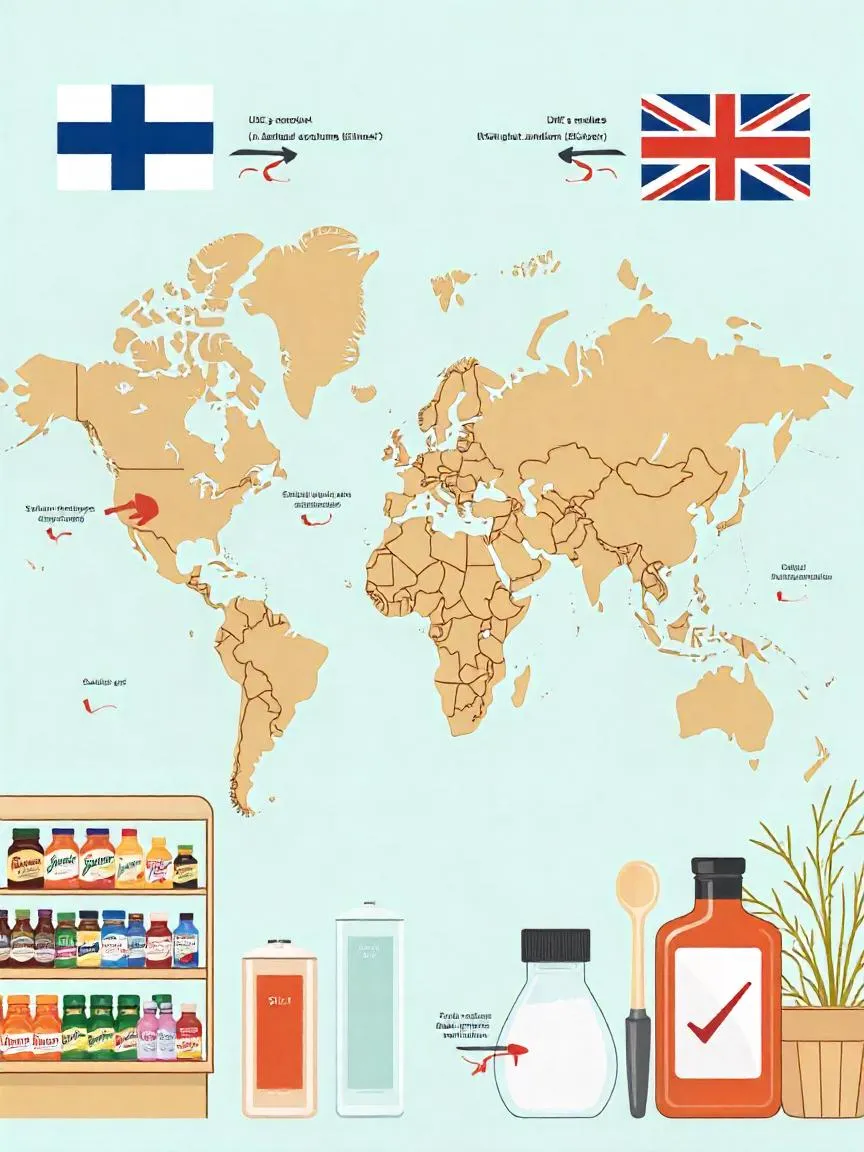

🌍 International Initiatives: Leading the Way in Sodium Reduction

Several countries have implemented effective national strategies to reduce sodium intake—proving that large-scale change is possible through a combination of policy, education, and industry collaboration.

🇫🇮 Finland: A Model of Government-Led Reform

- Finland launched a comprehensive sodium-reduction campaign involving:

- Public health education

- Mandatory warning labels on high-sodium foods

- Regulatory pressure on food manufacturers to reduce salt content

- Results:

- 30% reduction in daily sodium intake, from about 12,000 mg to 9,000 mg

- A measurable drop in average blood pressure and cardiovascular mortality

🇬🇧 United Kingdom: Industry and Government Collaboration

- The Consensus Action on Salt and Health (CASH), in partnership with the U.K. Department of Health, developed a voluntary salt reduction program.

- Their approach included:

- Setting salt-reduction targets for various food categories

- Monitoring food industry compliance

- Public awareness campaigns

- Outcomes:

- A 20–30% decrease in the salt content of processed foods sold in supermarkets

- Increased consumer awareness and demand for lower-sodium options

These international examples demonstrate that multi-pronged strategies—combining policy, education, and food reformulation—can significantly reduce population-level sodium intake and improve public health.